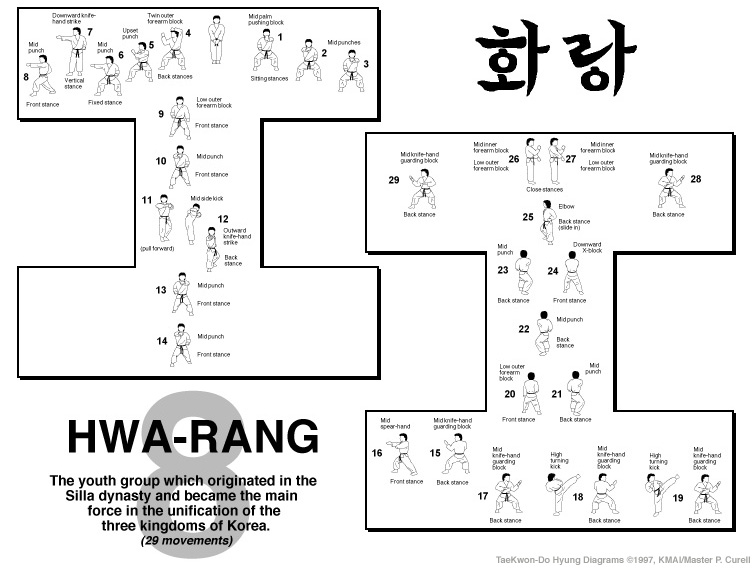

Movements - 29

Ready Posture - CLOSED READY STANCE C |

| 1. |

Step Right Foot into Square Horse Stance,

Left Palm Heel. |

| 2. |

Right Punch. |

| 3. |

Left Punch. |

| 4. |

Step to Right Back Stance to 3 oclock, C-Block.

|

| 5. |

Left Upper Punch. |

| 6. |

Right Inward Hammer. |

| 7. |

Hop up while Right Downward Knifehand Strike. |

| 8. |

Step to Left Forward to 3 oclock, Left Punch.

|

| 9. |

Step to Left Forward to 12 oclock, Left Downward

Block. |

| 10. |

Step to Right Forward Stance, Right Punch.

|

| 11. |

Steep Left Foot to Right, Chamber on Right.

|

| 12. |

Land in Left Back Stance, Right Shuto. |

| 13. |

Step to Left Forward Stance, Left Punch. |

| 14. |

Step to Right Forward Stance, Right Punch.

|

| 15. |

Step to Left Back Stance to 3 oclock, Left

Check. |

| 16. |

Step to Right Forward Stance, Right Spear. |

| 17. |

Step to Left Back Stance to 9 oclock, Left

Check. |

| 18. |

Right Round Kick, Land in Right Back Stance,

Right Check. |

| 19. |

Left Round Kick, Land in Left Back Stance,

Left Check. |

| 20. |

Step to Left Forward Stance to 6 oclock, Left

Downward Block. |

| 21. |

Right Punch, Shifting to Box Stance. |

| 22. |

Step to Right Back Stance, Left Punch. |

| 23. |

Step to Left Back Stance, Right Punch. |

| 24. |

Shift to Left Forward Stance, X-Downward block.

|

| 25. |

Step Right Leg Around, Right Hand Downward

Knife Block. |

| 26. |

Step Left to Right Foot, facing 9 oclock.

|

| 27. |

Scissor Blocks. |

| 28. |

Step to Left Back Stance to 9 oclock, Left

Outward Block. |

| 29. |

Shuffle to Right Back Stance to 3 oclock,

Right Outward Block. |

| END: Bring the right foot back to a ready

posture. |

HWA-RANG is named after the Hwa-Rang youth

group, which originated in the Silla Dynasty in the early 7th

century. The 29 movements refer to the 29th Infantry Division,

where Taekwon-Do developed into maturity.

The Beginning

The Hwarang were leaders of military bands of the Silla Dynasty.

They were chosen from the young sons of the nobility by popular

election. Each Hwarang group consisted hundreds or thousands

of members. The leaders of each Hwarang group, including the

most senior leader, were referred to as Kuk-Son. The Kuk-Son

was very similar to King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table

in England  around

1200. From their ranks were chosen government officials, military

leaders, field generals, and even kings who served Silla both

in times of peace and war. Most of the great military leaders

of Silla were products of Hwarang training, and many were Kuk-Son.

around

1200. From their ranks were chosen government officials, military

leaders, field generals, and even kings who served Silla both

in times of peace and war. Most of the great military leaders

of Silla were products of Hwarang training, and many were Kuk-Son.

Silla, established in 57 B.C., was the smallest of the three

kingdoms comprising what is now Korea. The citizens of Silla

were outnumbered and under continual threat of military domination

from the neighboring kingdoms of Paekche and Koguryo for over

700 years.

The Hwarang were established by Chin Hung, the 24th King of

Silla (540 A.D.), who was a devoted Buddhist and loved elegance

and physical beauty. He believed in mythical beings and male

and female fairies (Sin-Sun and Sun-Nyo). These beliefs led

him to hold beauty contests the prettiest maidens in the country,

which he called WonHwa (Original Flowers). He taught them modesty,

loyalty, filial piety, and sincerity so they would become good

wives. In one contest among 300-400 Won-Hwa, two exceptionally

beautiful young women were favored, Nam-Mo and Joon-Jung. Unfortunately,

the two began to struggle for power and influence between themselves.

Finally, in order to win the contest, Joon Jung got Nam-Mo drunk

and killed her by crushing her skull with a rock. When the unfortunate

maiden's body was found in a shallow grave by the river, the

king had Joon-Jung put to death and disbanded the order of the

Won-Hwa.

Several years after this incident the King created a new order,

the Hwarang. "Hwa" meant flower or blossom, and "Rang"

meant youth or gentle men. The word Hwarang soon came to stand

for Flower of Knighthood. These Hwarang were selected from handsome,

virtuous young men of good families. Their selection was carried

out by popular vote among their followers; then they were presented

to the king for nomination as a Hwarang or Kuk-Son. They learned

the five cardinal principles of human relations (kindness, justice,

courtesy, intelligence, and faith), the three scholarships (royal

tutor, instructor, and teacher), and the six ways of service

(holy minister, good minister, loyal minister, wise minister,

virtuous minister, and honest minister). The education of a

Hwarang was supported by the king and generally lasted ten years,

after which the youth usually entered into some form of service

to his country. King Chin Hung sent the Hwarang to places of

scenic beauty for physical and mental culture as true knights

of the nation. For hundreds of years the Hwarang were taught

by Kuk-Son in social etiquette, music and songs, and patriotic

behavior.

Buddhist philosophy

The Hwarang were taught the martial arts and Buddhist faith

and indoctrinated in the ways of cultured and chivalrous warriors.

They climbed rugged mountains and swam rapid rivers in all months

of the year, conditioning their minds and bodies for endurance

and discipline. Much of their training time was spent in the

mountains, at the seashore, and on wilderness excursions; training,

meditating, and composing songs and poetry. They were taught

dance, literature, arts, and sciences, and the arts of warfare,

charioteering, archery, and hand-to-hand combat. The hand-to-hand

combat was based on the Um-Yang principles of Buddhist philosophy

and included a blending of hard and soft, linear and circular

techniques. The art of foot fighting was known as Soo-Bak and

was practiced by common people throughout the three kingdoms.

However, the Hwarang transformed and intensified this art and

added hand techniques, renaming it Tae-Kyon. The Hwarang punches

could penetrate the wooden chest armor of an enemy and kill

him; foot techniques were said to be executed at such speed

that opponents frequently thought that the feet of Hwarang warriors

were swords. In later centuries the king of Koryo made Tae-Kyon

training mandatory for all soldiers, and annual Tae-Kyon contests

were held among all members of the Silla population on May 5th

of the Lunar Calendar.

The rank of Hwarang usually meant a man had achieved the position

of a teacher of the martial arts and commanded 500-5,000 students

called Hwarang-Do. A Kuk-Son was the master and held the rank

of general in the army. Hwarang fighting spirit was ferocious

and was recorded in many literary works including the Sam-Guk-Sagi,

written by Kim Pu-Sik in 1145, and the Hwarang-Segi. The latter

was said to have contained the records of lives and deeds of

over 200 individual l Hwa- sadly, it was lost during the Japanese

occupation in the 20th century.) The zeal of the Hwarang helped

Silla become the world's first ''Buddha Land" and led to;

the unification of the three kingdoms of Korea. Buddhist principles

were so ingrained in the code of the Hwarang that a larger number

of monks participated in the Hwarang-Do), and during times of

war they would robes and take up or ms to die for Silla.

The Hwarang code

The Hwarang code was established in the 3Oth year of King Chin-Hung's

rule. Two noted Hwarang warriors, Kwi-San and Chu-Hang, sought

out the famous warrior and Buddhist monk Wong-Gwang Popsa in

Kusil temple on Mount Unmun and asked that he give them lifetime

commandments that those men could follow who could not embrace

the secluded life of a Buddhist monk. The commandments, based

on Confucian and Buddhist principles, were divided into five

rules (loyalty to the king and country, obedience to one's parents,

sincerity, trust and brotherhood among friends, never retreat

in battle, and selectivity and justice in the killing of living

things), and nine virtues (humanity, justice, courtesy, wisdom,

trust, goodness, virtue, loyalty, and courage). These principles

were not taken lightly, as in the case of Kwi-San and Chu-Hang,

who rescued their own commander, General Muun, when  he

was ambushed and fell from his horse during a battle in 603

A.D. Attacking the enemy, these two Hwarang were heard to cry

out to their followers, "Now is the time to follow the

commandment to not retreat in battle!" After giving one

of their horses to the general, they killed a great number of

the pursuing enemy and finally, "bleeding from a thousand

wounds," they both died.

he

was ambushed and fell from his horse during a battle in 603

A.D. Attacking the enemy, these two Hwarang were heard to cry

out to their followers, "Now is the time to follow the

commandment to not retreat in battle!" After giving one

of their horses to the general, they killed a great number of

the pursuing enemy and finally, "bleeding from a thousand

wounds," they both died.

The code of the Hwarang is similar to the more commonly known

code of the Japanese samurai, Bushido. The Bushido code was

established in feudal Japan during the 12th to the 17th centuries

to serve as a social guide rule of life, and set of ideals for

the samurai or military class. The code of the Hwarang-Do played

a similar role in the Korean kingdom of Silla approximately

1,000 years earlier. Being established during the 6th to the

10th centuries, Hwarang-Do was considered more ancient and refined

than Bushido. The Silla Dynasty lasted 1,000 years, and the

Code of the Hwarang, known as Sesok-Ogye, endured throughout

the Silla and Koryo dynasties. Its influence led to a unified

national spirit and ultimately the unification of the three

kingdoms of Korea around 668 A.D. The practice of Bushido appears

to have perpetuated a feudal system in Japan for over 700 years

with continual provincial wars, whereas Silla and Koryo thrived

under the influence of the Hwarang. These Korean dynasties,

based on Hwarang ethics, remained internally peaceful and prosperous

for over 1,500 years while defending themselves against a multitude

of foreign invasions. This can be compared to the Roman Empire,

which thrived for only 1,000 years. Oyama Masutatsu, a well-known

authority on Karate in Japan, has even suggested that the Hwarang

were the forerunners of the Japanese samurai.

The first recorded Hwarang hero

Sul Won-Nang was elected as the first Kuk-Son or head of the

Hwarang order. But the first recorded Hwarang hero was Sa Da-Ham.

At the young age of 15 he raised his own 1,000-man army in support

of Silla in its war against the neighboring kingdom of Kara.

He requested and was granted the honor of leading this force

in support of the Silla army attacking the main fort of the

Kara in 562 A.D. As the first to breach the walls of the enemy

fort, he was highly praised and rewarded by King Chin Hung for

his bravery. He was offered 300 slaves and a large tract of

land as a reward, but released the slaves and refused the land,

stating that he did not wish to receive  personal

rewards for his deeds. He did agree to accept a small amount

of fertile soil as a matter of courtesy to the King. However,

when his best friend was killed in battle, Sa Da-Ham was inconsolable.

As a youth Sa Da-Ham and his friend had made pact-of-death should

either of them ever die in battle. True to his promise, Sa Da-Ham

starved himself to death demonstrating his loyalty and adherence

to the code of the Hwarang.

personal

rewards for his deeds. He did agree to accept a small amount

of fertile soil as a matter of courtesy to the King. However,

when his best friend was killed in battle, Sa Da-Ham was inconsolable.

As a youth Sa Da-Ham and his friend had made pact-of-death should

either of them ever die in battle. True to his promise, Sa Da-Ham

starved himself to death demonstrating his loyalty and adherence

to the code of the Hwarang.

The driving force in the unification of the Korean

Another legendary Korean was General Kim Yoo-Sin who became

a Hwarang at the age of 15 and was an accomplished swordsman

and a Kuk-Son by the time he was 18 years old. By the age of

34 he had been given the command of the Silla armed forces.

He is regarded as the driving force in the unification of the

Korean peninsula and the most famous of all the generals in

the unification wars. Kim Yoo-Sin was active on all fronts in

the wars, and at several times simultaneously conducted battles

against both Paekche and Koguryo. He defeated the great Paeckche

general Gae-Baek in the battle in which Gae-Back was killed.

Once, while Silla was allied with China against Paekche, a heated

argument began between Kim Yoo-Sin's commander and a Chinese

general. As the argument escalated into a potentially bloody

confrontation, the sword of Kim Yoo-Sin was said to have leaped

from its scabbard into his hand. Because the sword of a warrior

was believed to be his soul, this occurrence so frightened the

Chinese general blat he immediately apologized to the Silla

officers. Incidences such as this kept the Chinese in awe of

the Hwarang. In later years when asked by the Chinese emperor

to attack Silla, the Chinese generals claimed that although

Silla was small, it could not be defeated. Kim Yoo-Sin lived

to the age of 79 and is considered one of Korea's most famous

generals. He had five sons, who along with his wife contributed

great deeds to the historical records of the Hwarang.

Another

dedicated Hwarang, Kwan Chang, became a Hwarang commander at

the age of 16 and was the son of Kim Yoo-Sin's Assistant General

Kim Pumil. In 655 A.D., he fought in the battle of Hwangsan

against Paekche under General Kim Yoo-Sin. During this battle

he dashed headlong into the enemy camp and killed many Paekche

soldiers, but was finally captured. Ibis high ranking battle

crest indicated that he was the son of a general so he was taken

before the Paekche general, Gae-Baek. Surprised by Kwan Chang's

youthfulness when his helmet was removed, and thinking of his

own young son, Gae-Baek decided that instead of executing him

as was the custom with captured officers, he would return the

young Hwarang to the Silla lines. GaeBaek remarked, "Alas,

how can we match the army of Silla! Even a young boy like this

has such courage, not to speak of Silla's men." Kwan Chang

went before his father and asked permission to be sent back

into battle at the head of his men. After a day-long battle

Kwan Chang was again captured. After he had been disarmed, he

broke free of his two guards, killing them with his hands and

feet, and then attacked the Paekche general's second in command.

With a flying reverse turning kick to the head of the commander,

who sat eight feet high atop his horse, Kwan Chang killed him.

After finally being subdued once more, he was again taken before

the Packche general. This time Gae-Baek said "I gave you

your life once because of your youth, but now you return to

take the life of my best field commander." He then had

Kwan Chang executed and his body returned to the Silla lines.

General Kim Pumil was proud that his son had died so bravely

in the service of his king. He said to his men, "it seems

as if my son's honor is alive. I am fortunate that he died for

the King." He then rallied his army and went on to defeat

the Paekche forces.

Another

dedicated Hwarang, Kwan Chang, became a Hwarang commander at

the age of 16 and was the son of Kim Yoo-Sin's Assistant General

Kim Pumil. In 655 A.D., he fought in the battle of Hwangsan

against Paekche under General Kim Yoo-Sin. During this battle

he dashed headlong into the enemy camp and killed many Paekche

soldiers, but was finally captured. Ibis high ranking battle

crest indicated that he was the son of a general so he was taken

before the Paekche general, Gae-Baek. Surprised by Kwan Chang's

youthfulness when his helmet was removed, and thinking of his

own young son, Gae-Baek decided that instead of executing him

as was the custom with captured officers, he would return the

young Hwarang to the Silla lines. GaeBaek remarked, "Alas,

how can we match the army of Silla! Even a young boy like this

has such courage, not to speak of Silla's men." Kwan Chang

went before his father and asked permission to be sent back

into battle at the head of his men. After a day-long battle

Kwan Chang was again captured. After he had been disarmed, he

broke free of his two guards, killing them with his hands and

feet, and then attacked the Paekche general's second in command.

With a flying reverse turning kick to the head of the commander,

who sat eight feet high atop his horse, Kwan Chang killed him.

After finally being subdued once more, he was again taken before

the Packche general. This time Gae-Baek said "I gave you

your life once because of your youth, but now you return to

take the life of my best field commander." He then had

Kwan Chang executed and his body returned to the Silla lines.

General Kim Pumil was proud that his son had died so bravely

in the service of his king. He said to his men, "it seems

as if my son's honor is alive. I am fortunate that he died for

the King." He then rallied his army and went on to defeat

the Paekche forces.

The spirit of the Hwarang was present in all of the kingdoms

of Korea during this time, and although not as evident as in

Silla, it was demonstrated by such great Korean historical figures

as Yon-Gye, Ul-Ji Moon-Duk, and Moon- Moo This spirit was kept

alive throughout history by many individuals. Hwarang and the

martial arts fell out of favor during the Yi Dynasty (1392-1910)

and adherence to the  Hwarang

code declined. Several Koreans did keep the code, however, notably

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin who was instrumental in defeating the Japanese

invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. The spirit of the Hwarang

and their code was present in Buddhist temples by monks. For

example, in the 16th century two monks, Su San and who followed

the Hwarang code, rallied a Buddhist army that was instrumental

in driving the Japanese invasion forces from Korea

Hwarang

code declined. Several Koreans did keep the code, however, notably

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin who was instrumental in defeating the Japanese

invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. The spirit of the Hwarang

and their code was present in Buddhist temples by monks. For

example, in the 16th century two monks, Su San and who followed

the Hwarang code, rallied a Buddhist army that was instrumental

in driving the Japanese invasion forces from Korea

Stories of the Hwarang and their individual feats illustrate

the code of the Hwarang, the type of ethics and morality essential

to the evolution of the martial arts and the success Silla as

a nation. This code has profoundly affected the Korean people

and their culture throughout history. The lives and deeds of

the Hwarang illustrate a level of courage, honor, wisdom, culture,

compassion, and impeccable conduct that few men in history have

demonstrated. The dedication and self-sacrifice of the Hwarang

was clearly based on principles much stronger than ego and self

interest. This basis was the Sesok-Ogye, the code of the Hwarang.

Print

Pattern and History - 8/15/02

around

1200. From their ranks were chosen government officials, military

leaders, field generals, and even kings who served Silla both

in times of peace and war. Most of the great military leaders

of Silla were products of Hwarang training, and many were Kuk-Son.

around

1200. From their ranks were chosen government officials, military

leaders, field generals, and even kings who served Silla both

in times of peace and war. Most of the great military leaders

of Silla were products of Hwarang training, and many were Kuk-Son.

he

was ambushed and fell from his horse during a battle in 603

A.D. Attacking the enemy, these two Hwarang were heard to cry

out to their followers, "Now is the time to follow the

commandment to not retreat in battle!" After giving one

of their horses to the general, they killed a great number of

the pursuing enemy and finally, "bleeding from a thousand

wounds," they both died.

he

was ambushed and fell from his horse during a battle in 603

A.D. Attacking the enemy, these two Hwarang were heard to cry

out to their followers, "Now is the time to follow the

commandment to not retreat in battle!" After giving one

of their horses to the general, they killed a great number of

the pursuing enemy and finally, "bleeding from a thousand

wounds," they both died. personal

rewards for his deeds. He did agree to accept a small amount

of fertile soil as a matter of courtesy to the King. However,

when his best friend was killed in battle, Sa Da-Ham was inconsolable.

As a youth Sa Da-Ham and his friend had made pact-of-death should

either of them ever die in battle. True to his promise, Sa Da-Ham

starved himself to death demonstrating his loyalty and adherence

to the code of the Hwarang.

personal

rewards for his deeds. He did agree to accept a small amount

of fertile soil as a matter of courtesy to the King. However,

when his best friend was killed in battle, Sa Da-Ham was inconsolable.

As a youth Sa Da-Ham and his friend had made pact-of-death should

either of them ever die in battle. True to his promise, Sa Da-Ham

starved himself to death demonstrating his loyalty and adherence

to the code of the Hwarang. Another

dedicated Hwarang, Kwan Chang, became a Hwarang commander at

the age of 16 and was the son of Kim Yoo-Sin's Assistant General

Kim Pumil. In 655 A.D., he fought in the battle of Hwangsan

against Paekche under General Kim Yoo-Sin. During this battle

he dashed headlong into the enemy camp and killed many Paekche

soldiers, but was finally captured. Ibis high ranking battle

crest indicated that he was the son of a general so he was taken

before the Paekche general, Gae-Baek. Surprised by Kwan Chang's

youthfulness when his helmet was removed, and thinking of his

own young son, Gae-Baek decided that instead of executing him

as was the custom with captured officers, he would return the

young Hwarang to the Silla lines. GaeBaek remarked, "Alas,

how can we match the army of Silla! Even a young boy like this

has such courage, not to speak of Silla's men." Kwan Chang

went before his father and asked permission to be sent back

into battle at the head of his men. After a day-long battle

Kwan Chang was again captured. After he had been disarmed, he

broke free of his two guards, killing them with his hands and

feet, and then attacked the Paekche general's second in command.

With a flying reverse turning kick to the head of the commander,

who sat eight feet high atop his horse, Kwan Chang killed him.

After finally being subdued once more, he was again taken before

the Packche general. This time Gae-Baek said "I gave you

your life once because of your youth, but now you return to

take the life of my best field commander." He then had

Kwan Chang executed and his body returned to the Silla lines.

General Kim Pumil was proud that his son had died so bravely

in the service of his king. He said to his men, "it seems

as if my son's honor is alive. I am fortunate that he died for

the King." He then rallied his army and went on to defeat

the Paekche forces.

Another

dedicated Hwarang, Kwan Chang, became a Hwarang commander at

the age of 16 and was the son of Kim Yoo-Sin's Assistant General

Kim Pumil. In 655 A.D., he fought in the battle of Hwangsan

against Paekche under General Kim Yoo-Sin. During this battle

he dashed headlong into the enemy camp and killed many Paekche

soldiers, but was finally captured. Ibis high ranking battle

crest indicated that he was the son of a general so he was taken

before the Paekche general, Gae-Baek. Surprised by Kwan Chang's

youthfulness when his helmet was removed, and thinking of his

own young son, Gae-Baek decided that instead of executing him

as was the custom with captured officers, he would return the

young Hwarang to the Silla lines. GaeBaek remarked, "Alas,

how can we match the army of Silla! Even a young boy like this

has such courage, not to speak of Silla's men." Kwan Chang

went before his father and asked permission to be sent back

into battle at the head of his men. After a day-long battle

Kwan Chang was again captured. After he had been disarmed, he

broke free of his two guards, killing them with his hands and

feet, and then attacked the Paekche general's second in command.

With a flying reverse turning kick to the head of the commander,

who sat eight feet high atop his horse, Kwan Chang killed him.

After finally being subdued once more, he was again taken before

the Packche general. This time Gae-Baek said "I gave you

your life once because of your youth, but now you return to

take the life of my best field commander." He then had

Kwan Chang executed and his body returned to the Silla lines.

General Kim Pumil was proud that his son had died so bravely

in the service of his king. He said to his men, "it seems

as if my son's honor is alive. I am fortunate that he died for

the King." He then rallied his army and went on to defeat

the Paekche forces. Hwarang

code declined. Several Koreans did keep the code, however, notably

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin who was instrumental in defeating the Japanese

invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. The spirit of the Hwarang

and their code was present in Buddhist temples by monks. For

example, in the 16th century two monks, Su San and who followed

the Hwarang code, rallied a Buddhist army that was instrumental

in driving the Japanese invasion forces from Korea

Hwarang

code declined. Several Koreans did keep the code, however, notably

Admiral Yi Sun-Sin who was instrumental in defeating the Japanese

invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. The spirit of the Hwarang

and their code was present in Buddhist temples by monks. For

example, in the 16th century two monks, Su San and who followed

the Hwarang code, rallied a Buddhist army that was instrumental

in driving the Japanese invasion forces from Korea